Sports Science with Dr. Jeff Leiter | Game On Magazine

Photos courtesy of RINK

The on-ice beep test was developed almost 10 years ago as a more sport-specific measure of aerobic fitness (power) than the bike or treadmill tests that were commonly used at National Hockey League (NHL) training camps. Aerobic power, or VO2max is the maximum amount of oxygen an individual can use per minute and is an important measure for athletes that compete in distance events such as running, swimming, cycling and cross-country skiing. Although hockey is a fast game that requires physical strength and power, up to one-third of the energy demands of a hockey game come from the aerobic system (Montgomery, 1988). Aerobic power has also been used to predict scoring chances (Nobes, 2003) and is positively correlated with skating speed (Green, 2006).

Regardless of the test used, in order to be a valid measure of aerobic power, athletes must reach near maximal heart rates and a state of exhaustion (i.e. inability to continue exercise even if they want to). In other words, the tests must elicit extreme discomfort for a sustained period of time.

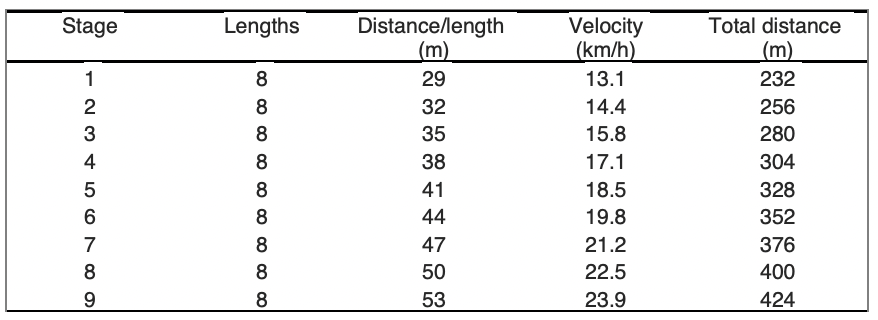

Table 1.

The on-ice beep test was designed to mimic a hockey game. The test is broken down into stages and levels (Figure 1). Each stage consists of 8 levels and a player has 8 seconds to complete each level (Figure 2). After the stage is complete, players rest for 60 seconds before attempting the next stage. As players advance to the next stage, the distance of each level increases by 3 meters and therefore, players must skate faster (Table 1).

To date, over 1000 on-ice beep tests have been administered to NHL, AHL, WHL and CSSHL (i.e. U15, U15 Prep, U16 Prep, U17 Prep, U18 Prep and U18 Female Prep) players. Regardless of level, players are extremely anxious prior to testing, and exhausted afterwards. It is a true measure of aerobic power and several psychological and motivational factors that allow players to overcome central (cardiorespiratory) and peripheral (local muscular) discomfort. As one NHL player said to me “I ‘beepin’ hate you, well….I don’t hate you but I hate this ‘beepin’ test”.

Players that achieve the highest score on the on-ice beep test are usually the top players on the team which confirms that aerobic power is essential to play hockey at a high level. For example, players that complete level 7 can sprint up and down the ice at a speed of 21.2 km/h for over a minute. And as the old saying goes “forecheck, backcheck, pay cheque”.

The highest score ever recorded by an NHL player was stage 9 and level 3. That’s skating the full length of the ice in under 8 seconds and doing it 3 times in a row with no rest. Now that’s fast, and that’s fit!

PRO TIP: Preparation is key

- Whether it’s off or on ice testing, ask the coaches what tests are required for training camp when you first receive the invite. Don’t ask a few days before camp. You want to prepare for testing in the off-season to ensure you will perform to the best of your ability.

- If it’s a maximal exertion test, such as the on-ice beep test, get comfortable with feeling discomfort. There are several maximal exertion tests that can be performed on a stationary bike or treadmill if you don’t have access to ice. Practice and develop strategies to distract your mind from the physical discomfort.

- Be excited about the experience. It’s an opportunity to show coaches and management that you are prepared, well-conditioned and ready to go for the hockey season!

Table 1. On-ice beep test. Each stage consists of 8 lengths for a total of 64 seconds of skating time. There is a 60 second rest between each stage.

References

- Montgomery, D. Physiology of ice hockey. Sports Med 5: 99, 1988.

- Nobes, KJ, Montgomery, DL, Pearsall, DJ, Turcotte, RA, Lefebvre, R, and Whittom, F. A comparison of skating economy on-ice and on the skating treadmill. Can J Appl Physiol 28:1-11, 2003.

- Green, MR, Pivarnik, JM, Carrier, DP, and Womack, CJ. Relationship between physiological profiles and on-ice performance of a National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I hockey team. J Strength and Cond Res 20: 43-46, 2006.

Written for Game On Magazine | https://gameonhockey.ca/